Texana Classics 7

Books That Matter in Editions That Inspire

Thomas Bangs Thorpe (1815-1878)

OUR ARMY ON THE RIO GRANDE, BEING A SHORT ACCOUNT OF THE IMPORTANT EVENTS TRANSPIRING FROM THE TIME OF THE REMOVAL OF THE “ARMY OF OCCUPATION” FROM CORPUS CHRISTI, TO THE SURRENDER OF MATAMOROS, WITH DESCRIPTIONS OF THE BATTLES OF PALO ALTO AND RESACA DE LA PALMA, THE BOMBARDMENT OF FORT BROWN, AND THE CEREMONIES OF THE SURRENDER OF MATAMOROS: WITH DESCRIPTIONS OF THE CITY, ETC.

Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1846. [Verso of title page:] Stereotyped by Jos. C. D. Christman. T. K. & P. G. Collins, Printers.

Adversaries in the U.S.-Mexican War (1846-1848) fought over the southern boundary of Texas; the first four engagements—the Thornton Affair, the siege of Fort Texas, the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma–occurred on what is now Texas soil. Yet, for thirty-five years my students, in Texas colleges and universities, continually conflated the conflict with the Spanish-American War (1898). Americans, across a wide demographic spectrum, recall the pivotal war in error, or else have forgotten it all together.

If more people were aware of it, Thomas Bangs Thorpe’s Our Army on the Rio Grande might provide a corrective. He was a polymath, distinguished as a graphic artist, author, reporter, and humorist. A native of Westfield, Massachusetts, he was the son of the Reverend Thomas and Rebecca (née Farnham) Thorp. His father died when the boy was four years of age and the family, which by then included two younger siblings, shifted to Albany, New York, residing with his mother’s parents.

Early on, Thomas showed promise. At the tender age of sixteen, he painted a canvas portraying Washington Irving’s “Bold Dragoon” (I.E., Ichabod Crane from the short story, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.”) Following its exhibition at the New York Academy of Fine Arts, it hung in Irving’s Tarrytown home. Sometime following his initial success, he added the “e” to his surname. In 1833, Thorpe traveled to Middleton, Connecticut, to attend Wesleyan University. Owing to poor health, he abandoned his studies during his junior year and moved to Louisiana.

Thorpe’s time in the Pelican State witnessed his greatest output. He published five newspapers, chiefly in New Orleans and Baton Rouge. Moreover, his short story, “The Big Bear of Arkansas” (published in 1841 in the New York City magazine Spirit of the Times) gained commendation as the first specimen of genuinely “Western” humor. Not only did he craft an engaging narrative, but he also “sustained a continuous and racy exaggeration that marked a new phase in American humor.” The tale became so popular that literary critics identified Thorpe’s southwestern colleagues as members of the “Big Bear school.” One authority placed Thorpe among the “most effective portrayers of American frontier life and character before Mark Twain.” High praise, indeed.

Only a year after the publication of Our Amy on the Rio Grande, critic R. W. Griswold lauded Thorpe in his book, Prose Writers of America: “He has a genuine relish for the sports and passion of southern frontier life, and describes them with remarkable freshness and skill of light and shade. No one enters more heartily into all the whims and grotesque humours of the backwoodsman, or brings him more actually or clearly before us.”

But Our Army on the Rio Grande is not a humor piece, no more than it is a work of history. Rather, it is eye-witness reportage from a spectator deeply involved in the outcome of his story. While in Louisiana, Thorpe became an important person who rubbed shoulders with other movers and shakers, among whom was General Zachary Taylor. In pursuit of a juicy story, Thorpe did not hesitate to employ those contacts. In May 1846, Thorpe left New Orleans on a ship bound for the Rio Grande. Signifying the trust army officials had for this civilian, they solicited him to carry dispatches to his friend General Taylor. Arriving at Taylor’s camp, Thorpe received permission to remain as a correspondent for the New Orleans Daily Tropic (of which he was a co-owner).

With the Mexican ambush and defeat of Captain Seth Thornton’s patrol, fighting broke out on the north bank of the contested stream. Next came the bombardment of Fort Texas, across the river opposite the Mexican town of Matamoros. While the U.S. garrison resisted against long odds, Taylor marched his army southward from Port Isabel intent on breaking the siege. Anticipating such a move, on May 8 General Mariano Arista intercepted Taylor’s force on the plains of Palo Alto. Largely because of the efficacy of his artillery, Taylor trounced Arista’s numerically superior force. As he did the following day at Resaca de la Palma. Thoroughly routed, Arista abandoned Matamoros and initiated a hasty retreat into the Mexican interior.

Describing his experiences, Thorpe explained: “The author was among those who were deeply excited by the stirring incidents connected with our little army on the Rio Grande, in the months of April and May, 1846, and he was on the battle fields, and among the heroes, almost immediately after the occurrences that have rendered them immortal in the history of the country. The idea of writing the following little volume was suggested by the accumulation of materials, collected for the transient purpose of varying the columns of a daily paper.” Thorpe gratefully acknowledged the support of General Edmund Pendelton Gaines (who features prominently in the pages of my book, Texian Exodus: The Runaway Scrape and its Enduring Legacy) and General William J. Worth (namesake of the frontier post and subsequently the municipality of Fort Worth).

The volume is rich with anecdotes. Thorpe recognized the exceptional character of the Texas Rangers serving with Taylor’s army. In fact, Our Army on the Rio Grande first introduced the unit to Americans living in the “old states.” He included a sketch that illustrated their wry sense of humor: “Among the Texas Rangers, ‘winning a saddle,’ means, taking one from a Mexican. On the 8th, when Gen. [Anastasio] Torrejon charged with his cavalry, a Mexican officer and horse fell upon the field. A Texian dismounted amidst the very charge, and in an instant almost, transferred the officer’s saddle to his own horse, and left his own in its place, saying, that if it was not a fair exchange, the owner might come to him, and he would pay the difference.”

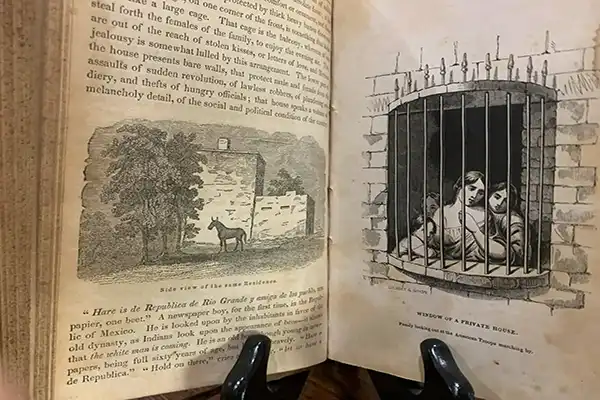

In June, Thorpe made his way back to New Orleans where, at breakneck speed, he began writing. As early as June 16, he sent manuscript pages to his publishers, Carey and Hart. In a June 25 letter to them, he crowed: “I believe I shall give you one of the most readable books of the season. . . . I have been over the whole ground . . . kept a voluminous journal etc. . . . I shall have the only descriptions of the battles and subsequent scenes ever published.” In addition to his narrative, he also supplied lithograph illustrations, rendering the work more useful than it would have been otherwise. Obviously, both the author and his publishers wished to scoop the competition. Early in October 1846, Carey and Hart released the book to the public–a turnaround any modern author would envy.

It was too hurried. As Thorpe’s biographer Milton Rickels noted: “The writing itself shows signs of haste in composition, both in language and structure, but the narrative generally moves easily and is lively and colorful.”

The bookman and bibliophile John H. Jenkins thought Our Army on the Rio Grande so essential that he included it in his Basic Texas Books: An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Works for a Research Library (1983). Still, Jenkins expressed misgivings concerning what he viewed as the author’s deficiencies. “The volume,” he pronounced,” is marred by Thorpe’s conventional attitude towards the war and his blind acceptance of American manifest destiny. The Americans meet battle ‘with eyes flashing with enthusiasm, and a proud consciousness of coming victory,’ and are ‘children of destiny . . . the passive instruments in the hands of an overruling power to carry out its great designs.’”

Marred? I strongly disagree. A primary account’s value lies in its ability to allow modern readers into the minds of individuals long dead, to know their partialities, to learn their virtues and vices. It is a conversation from the grave. Thorpe breathed the air of his times; he took a side and echoed the sensibilities of his contemporaries. While essential in academic historians, it demands too much of human nature to demand “objectivity’ from those who invested themselves in the great issues of their day. Listening to lectures on Manifest Destiny, my students frequently asked, “How could they have believed that?” In Our Army on the Rio Grande, Thorpe answers that question.

If readers seek balance, they can (and should) consult other period perspectives. They might, for example, examine Henry David Thoreau’s essay “Resistance to Civil Government” (also known as “Civil Disobedience”), a fiery denunciation of the Mexican War and the notion of Manifest Destiny. Let Thorpe be Thorpe and Thoreau be Thoreau. But for Heaven’s sake—for history’s sake—do not attempt to affix twenty-first century tenets of “objectivity” onto those who inhabited the nineteenth-century. Not only is it demonstrably unfair, but it is also ahistorical.

Thorpe followed up Our Army on the Rio Grande with two other volumes: Our Army at Monterey (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1847), which incorporated useful information on the contributions of Texas troops, and The Taylor Anecdote Book: Anecdotes and Letters of Zachary Taylor (New York: D. Appleton, 1848). Notwithstanding time spent in the sunny southland, Thorpe remained at heart a Massachusetts Yankee and abolitionist. In 1853, Thorpe abandoned Louisiana and returned to New York. He remained active in publishing and public life until his death in 1878.

Those wishing for additional information on Thorpe’s life and works will benefit from Milton Rickels’s biography, Thomas Bangs Thorpe: Humorist of the Old Southwest (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1962).