Texana Classics 6

Books that Matter in Editions That Inspire

James Frank Dobie.

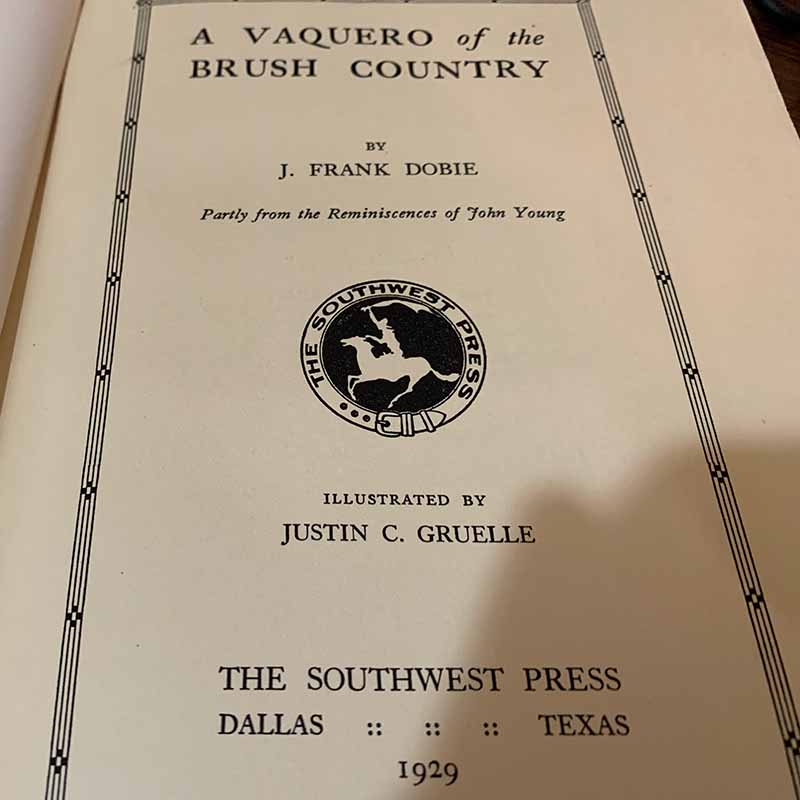

A VAQUERO OF THE BRUSH COUNTRY.

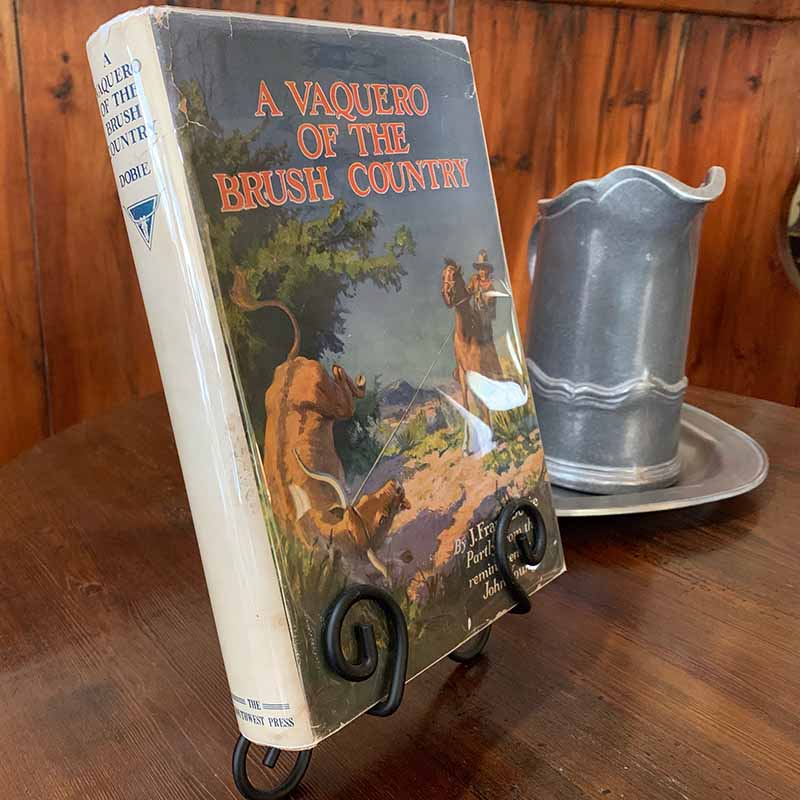

Dallas: The Southwest Press., 1929. Illustrated by Justin Gruelle. XV, 314 pp. Six plates. Map end papers. 24 cm. Cloth-backed boards, dust jacket. 2000 copies printed.

Click each image to open a Lightbox for high resolution viewing.

A Vaquero of the Brush Country has never been my favorite in J. Frank Dobie’s oeuvre. That honor belongs to Coronado’s Children, which he published the following year. Even so, his first book contains much of interest and value. In 1983, John H. Jenkins included it in Basic Texas Books: An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Works for a Research Library. In that authoritative volume, Jenkins extolled it as “a lasting contribution to the literature of the Texas range.” Literary critic Henry Nash Smith thought it a “history which is at the same time a personal expression and a prose poem. . . . What fund of erudition and what countless strokes of art have gone into this easy-going, even homely narrative.”

Published in 1929, the entire course of Dobie’s life had led him to write this book. In 1888, Dobie, the eldest of six children, was born on a working ranch in Live Oak County, Texas. He enrolled at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas, in 1906. There he developed a lifelong fascination with English literature. While attending Southwestern, he also met Bertha McKee (1890-1974), who shared his passion for books and poetry; they married in 1916. Following graduation from Southwestern, Dobie wrote for newspapers in San Antonio and Galveston. Because of the low wages, he abandoned journalism and accepted a position teaching high school English in Alpine, Texas.

There in “The Heart of the Big Bend,” Dobie became acquainted with John Duncan Young, who in his youth had been a South Texas cowboy. The English teacher became fascinated with Young’s tales of gun smoke and saddle leather, many of which revolved around late-nineteenth century Live Oak County. Dobie filed the stories away in his memory; eighteen years later they would form the basis of Vaquero.

In 1911, Dobie abandoned Alpine, returning to Georgetown to teach at Southwestern Preparatory School. He soon discovered that teaching high school was not to his taste and, in 1913, traveled to Columbia University to pursue a master’s degree. The following year, master’s degree in hand, he returned to Austin to join the English faculty at the University of Texas and began a life-long association with the Texas Folklore Society. In 1917, when the United States entered the Great War, he left Texas to serve in the field artillery. Dobie saw brief action in France during the last days of the conflict and received an honorable discharge in 1919.

Back in Austin with Bertha, Dobie began to grind out articles about Texas cowboys and Longhorn cattle mostly for popular magazines. Dobie proved remarkably indifferent to writing the sort of pieces calculated to advance his academic career. In 1920, disgusted with the academic fussbudgetry, he left the university to work on his uncle’s ranch in La Salle County, Texas.

Toiling on the ranch for a year taught Dobie a valuable lesson. Despite his South Texas roots, he was no ranchman. He enjoyed writing about cowboy life far more than he did living the cowboy life.

In 1920, Dobie, chastened but unbowed, returned to Austin where he employed the university’s extensive holdings to write about the folklore of the open range—once again for popular magazines, not scholarly journals. In 1922, he became the secretary-editor of the Texas Folklore Society, a post he held for the next twenty-one years. The stiff-necked instructor doggedly refused to pursue the terminal degree. Told that he would not gain promotion without a Ph.D., he accepted the position of chair of the English Department at Oklahoma A&M College. While in Stillwater, he wrote a number of pieces for Country Gentleman—another periodical unlikely to endear him to stuffy scholars. Nevertheless, with the assistance of several Austin colleagues, he received a token promotion and returned to UT in 1925. Dobie, still refusing to work toward a Ph.D., became one of the university’s better known professors because of his heavy output of “popular” articles.

Dobie’s position at UT was far from secure. While admired by students and the public, many inside the English department considered him a dilettante. With the “Roaring Twenties” rushing to a close, Dobie was approaching his forties. He was far from old, but it was time (past time, really) to make his mark on his chosen profession. He had published an overabundance of non-academic articles but he needed a book—something of substance. He had never forgotten the stories of his Alpine running buddy, John D. Young. He contacted the old cowboy and suggested that they turn the events of his early life into a sort of memoir.

Young enthusiastically agreed. Dobie later asserted that he and Young “made medicine.” A stranger to the world of books and publishing, Young was more than a little naïve concerning his cut of the anticipated royalties. He believed that the proceeds would fund the construction of a ten-story marble hotel in the heart of San Antonio. Apparently, Dobie never attempted to dissuade the ageing cowpoke of his unrealistic expectations. Young envisioned a book in which he’d be the hero of his own story. He trusted Dobie to do the writing based on his anecdotes; Dobie had something else in mind.

Dobie opted to publish with the brand new Southwest Press of Dallas, which was an effort to institute a self-sustaining publishing house inside Texas. A laudable goal, but Dobie had another reason for publishing with Southwest Press. He was a stockholder, a detail he may not have shared with his partner.

When the book arrived in 1929, it was a minor regional hit. Still, it was not the memoir Young expected. As Dobie explained, “I made him more a figure of the earth than the hero of his own imagination.” Instead of telling the rootin’-tootin’ tale of a young cowboy, the author represented him as a “representative of the unfenced world.” The college professor wished to paint on a larger canvas: “the brush and the brush land [which] has never been written.” Journalist Lon Tinkle observed that “the association did not ‘fully satisfy’ Mr. Young, either financially , , , or personally or professionally, since Dobie emphasized the ‘sociology’ of ranching far more than Mr. Young’s individual experiences.” Historian Eugene C. Barker wrote approvingly: “The method of the book is to weave into the reminiscences of John Duncan Young a comprehensive study of many phases of the cattle business.” Young thought Dobie’s “method” needlessly highfalutin.

Southwest Press had a print run of two thousand copies and in its first year sold almost one thousand. Not a bad outing for a first-time non-fiction author. But the proceeds were not nearly enough for Young’s fantasy hotel. The timing couldn’t have been worse. During the first year of the Great Depression, few folks were funding any construction projects. Young believed he had been hoodwinked. The title page seemed to add insult to injury. It read A Vaquero of the Brush Country by J. Frank Dobie. Then, under the author’s name—almost as an afterthought—“Partly from the Reminiscences of John Young.” Partly? Young had believed the book was going to be entirely about him.

At this distance, and without further documentation concerning the “medicine” the pair made, it is difficult to assess blame. Was Dobie guilty of duplicity, or did Young have unrealistic expectations from the beginning? What is known is that for years afterward bad blood simmered. Young and his heirs harbored a growing resentment toward Dobie.

Indeed, in recent years, Young’s descendants demanded that the University of Texas Press (who keep the Dobie cannon in print) name Young as the primary author, consigning Dobie to a secondary status. Incredibly, the suits at the press caved. They even changed the title to A Vaquero of the Brush Country: The Life and Times of John D. Young and now list the authors as “John D. Young and J. Frank Dobie.”

What an incandescently stupid judgement. Every scholar who has ever studied the issue established that Dobie was the rightful author. It is probable that Young never “wrote” a single word. Of course, he told colorful stories, but colorful stories do not a book make. Dobie actually put in the hard-chair time at the typewriter: if he hadn’t the book would have never existed. At its core, the volume presented Young’s recollections. Nonetheless, if Young supplied the apple’s seeds and core, Dobie delivered the flesh, skin, and stem.

Still, if one is to credit Dobie as the author (and I do), one must also hold him accountable for the volume’s flaws. Jenkins remarked on the muddle that the dueling narrators created. “Thus a book was created that to some readers is a perfect blend, and to others a confusing mixture of an old cowman and a college professor. Dobie allows the narrative to flow in the first person as though by Young, but the wording and indeed many whole sections are entirely from the mind of Frank Dobie.”

Dobie would have argued that he was an artist experimenting with style, attempting a “personal expression and a prose poem.” Yet, the result is, from a historian’s perspective, a bit disingenuous. As Jenkins protested: “I want to know what John Young thought and said, in his own words, and I also want to know what Frank Dobie had to say about them, with all his amplifications—but in this book Dobie’s own genius runs roughshod over all else. It is Dobie’s book, and Dobie’s point of view, in spite of the technique of letting the old cowman appear to do the talking.” Dobie may, or may not, have been deceitful in his dealings with Young, but he was certainly guilty of intellectual self-aggrandizement.

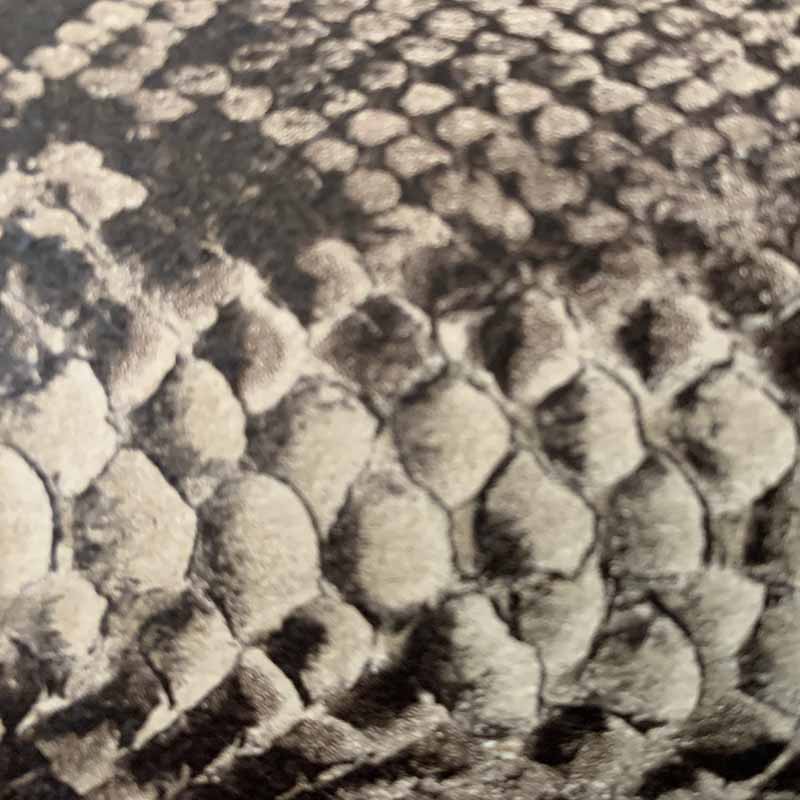

Through the good graces of David Pratt of Pratt’s Books in Graham, Texas, I have recently acquired a 1929, Southwest Press, first edition of Vaquero—complete with the original dust jacket. Nowadays, it is difficult to locate a first edition, but to find one with the dust jacket is practically unheard of. I had never even seen one until I bought David’s copy. One of the characteristics of the Southwest Press edition are the boards bound in imitation rattlesnake skin. The operative word is imitation. In hindsight, it was not a prudent choice. The faux rattlesnake hide is actually nothing more that colored paper and does not stand the rigors of repeated readings or even time on the shelf. Most copies that I’ve inspected are distinctly tatty in their appearance. Not mine. The boards show a bit of shelf-burn and the dust jacket shows some chipping but it remains in remarkably good condition for a volume published when Herbert Hoover still occupied the Oval Office. It’s the tightest first edition I’ve ever seen. I will strive to preserve this remarkable copy for future generations of bibliophiles.