William Fairfax Gray:

His Insightful Eye and Perceptive Pen

Among the fifty-nine delegates assembled at the Town of Washington for the 1836 Texas Independence Convention, was one who did not participate in the proceedings, but merely observed them. Yet, he did far more than merely observe. He scrutinized his world with the meticulousness of a microscope and the sagacity of a Tocqueville. William Fairfax Gray, a Virginia visitor, had applied for the position as convention secretary but Texian officials rejected his bid. Undeterred, he nonetheless kept his own record of the convention, which Professor Andrew Forrest Muir observed was “in some cases more complete than the official record.” Bibliophile and scholar John H. Jenkins remarked, “Gray left us the best account of events in Texas during the revolution written as they occurred.” Jenkins identified the essential contribution of Gray’s writing. It was not the reminiscence of some hoary headed geezer decades after events, but rather recorded in the moment. Historian T. R. Fehrenbach lamented participant recollections “tend to be self-serving and must be suspect. But Gray wrote spontaneously about people with whom he had no previous contact, and his impressions, although acquired on short acquaintance, add greatly to our understanding of the key men in the great drama unfolding around him.” One fact is indisputable; without Gray’s diary our knowledge of Texas political, military, and social history would be immeasurably diminished.

Gray’s background had prepared him for his chronicler role. The son of William and Catherine Gray, he was born on November 3, 1787, in Fairfax County, Virginia. The Grays may not have been among the first families of Virginia, but they travelled in the same circles. Young Gray corresponded and did business with founding fathers Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. On March 21, 1811, he attained the rank of captain in the Sixteenth Regiment of the Virginia Militia, just in time to see active service in the War of 1812. Following the resolution of that conflict, he won a commission as a lieutenant colonel. For the rest of his life he enjoyed the honorific title of “colonel,” although his growing family prevented his active military service.

Gray postponed matrimony until he was financially secure. His choice of a bride, however, more than justified the wait. On September 24, 1817, he married Mildred (family members knew her as “Millie”) Richards Stone. Seventeen years of age at the time, she was the daughter of William Scandrett Stone, who had formerly served as mayor of Fredericksburg, Virginia, their hometown. It was a good match. The couple shared an interest in music, despite the steady loss of Millie’s hearing. She consistently faced life’s difficulties with remarkable steadfastness. Their union produced twelve children but half of them died in infancy. When William lost his position, Millie proved an able helpmate. She supplemented the family income by offering piano lessons, took in seamstress work, laid off household servants, and personally took on domestic chores.

In 1834, Gray’s finances suffered a devastating reversal. William became a victim of President Andrew Jackson’s “Spoils System,” which favored partisans of “Old Hickory’s” Democratic party. On January 7, 1834, he lost his place as postmaster–along with his salary–and quickly plummeted into bankruptcy. By the end of April, penury had forced him to place the family home, household furniture, and even domestic servants on the auction block. Yet, the Grays were fortunate in their friends and relatives. A well-heeled cousin Thomas Green (more about him later) purchased many of the auction items and generously returned them to the family. William and Millie probably thought they had hit rock bottom. They were wrong. In July, their one-month-old daughter died. Despite his best efforts, William was unable to pull out of the economic spiral. In January 1835, circumstances forced William to part with most of his library, volumes that had survived the 1834 auction. William and Millie, once one of Fredericksburg’s golden couples, had sunk to poor relative status.

William never succumbed to despair. From November 1834 until March 20, 1835, he attended law lectures. Highly motivated, he studied assiduously, securing his license to practice law on May 4. Never again would he rely on patronage to make his living.

But the newly minted barrister did not hang up a shingle. Instead, he worked exclusively for the partnership of Thomas Green and Albert T. Burnley. Recall Green was the cousin who had come to his assistance during the 1834 auction. Like so many Americans of the time, Green and Burnley speculated in western lands. And that’s where Gray entered the equation. The partners tasked Gray with a search for fertile land at bargain prices in the Old Southwest and Mexican Texas. Much depended on Gray’s acumen and judgement. His employers authorized him to secure land titles and make profitable deals. Green may have trusted Gray, but gave him highly specific directions: “Get all the information about Texas lands. . . . Do not be in too great a hurry, but examine well, and be very particular. . . . Keep a diary.” It is probable that without Green’s directive, Gray would not have kept such a careful log of his travels.

Green and Burnley had hauled Gray out of a deep financial pit and given him hope for a brighter future. William was, of course, enormously grateful to the partners and vowed not to let them down. But he also realized that all their fortunes were intertwined. While buying land for the company, he also sought acres on which he could relocate his family. The assignment promised abundant opportunities but also considerable hardship. William would be gone for months, during which Millie would be on her own to maintain their household. A week before her husband left on his journey, Millie wrote, “We hear of a great many persons emigrating, and I reckon we shall go too some day or other.” The tone suggested the prospect did not thrill her.

The timing for a business trip could not have been worse. The “Come and Take It” fight at Gonzales occurred on October 2, 1835–four days before Gray began his journey. By the time he arrived in Texas on January 28, 1836, the place was roiling with dismay, dissension, and discord. In such a climate, the chief ambition of his trip–acquiring acres for Green, Burnley, and himself–had become a forlorn hope. Still, he refused to return to Virginia empty handed. He remained in Texas to learn the lay of the land, study the local economy, and represent Green and Burnley. With an exhibition of faith, persistence, and pluck he trusted that the wheel of fortune would turn full circle.

Learning that delegates from the various Texian settlements were to convene at the Town of Washington on March 1 to organize a new government, Gray determined to place himself at the center of the action. Where better to protect the interest of his clients–not to mention his own? Typical of his work ethic, Gray arrived in Washington on February 27, well ahead of most Texian delegates.

The rustic Brazos River settlement failed to impress the Virginia visitor. Indeed, he labeled the place “disgusting”:

It is laid out in the woods; about a dozen wretched cabins or shanties constitute the city; not one decent house in it, and only one well defined street, which consists of an opening cut out of the woods. The stumps still standing. A rare place to hold a national convention in. They will have to leave it promptly to avoid starvation.

On March 1, delegates opened the Convention and declared independence on March 2. Some claimed Tennessee native George C. Childress had arrived in Washington with a draft of the declaration of independence in his saddlebags. It was not a highly deliberative process. Never had so many politicians weighed so quickly a question of such momentous importance. Amidst a swirl of commotion, conflict, and chaos, representatives signed into existence the Republic of Texas and ushered in a decade of sovereignty singular in the annals of U.S. history. Gray may not have been a delegate himself, but modern Texans are fortunate that he was present to so carefully document the event for posterity.

In the pages of his diary, Gray frequently appears as a hopeless prig. He was a proud Virginian and measured Texas people, places, and procedures by Old Dominion standards–and found them wanting. Here, for example, are his thoughts on Convention President Richard Ellis: “The President is losing ground. He made a good impression at first, but by his partiality and weakness and great conceit he has forfeited the respect of the body, and a laxity of order begins to become apparent.” Nor did he have a high opinion of the delegates as a whole: “Such miserable narrow mindedness is astonishing. There is a great want of political philosophy and practical political knowledge in the body.” Gray was a devout and practicing Christian and it horrified him that most Texian delegates were not. March 13 had been a Sunday, and he was aghast that the “Convention continued their business as usual, without regard for the day. Indeed I have seen little or no observance of the day in Texas.” In general, he found Texians “a most ungodly people.”

Once the delegates declared Texas independent, they had to construct a government for the infant nation. They lingered in Washington until March 17, framing a constitution. Predictably, Gray disparaged their efforts. He proclaimed the new charter, “awkwardly framed, arrangement and phraseology bad; general features much like that of the United States.” When delegates finished drafting the constitution, they dissipated like dandelion seeds in a high wind. “The members are now dispersing in all directions,” Gray wrote, “with haste and confusion. A general panic seems to have seized them. Their families are exposed and defenseless, and hundreds are moving off to the east.” Texian evacuees recalled the “general panic” as the Runaway Scrape.

Among those “moving off to the east” was Ad Interim President David G. Burnet and his entire cabinet. Gray accompanied government officials as they abandoned Washington and fled toward the settlement of Harrisburg on Buffalo Bayou. Yet, they remained there only a brief time before the advance of Mexican troops forced their evacuation to Galveston Island. At that juncture, it looked as if circumstances had dashed all Texian dreams of independence.

Consequently, he was glad to wipe the mud of the fledgling republic off his brogans and return to Virginia. Officials of the Texas Republic granted him a passport and, on April 24, he was on the road back to Virginia when he received news of the almost miraculous Texian victory at San Jacinto. Therefore, it was with a glad heart that he travelled back to Fredericksburg to rejoin Millie and the surviving children. He also reported to Green and Burnley, who must have found the thoroughness of his accounts impressive.

Notwithstanding his many reservations regarding Texas, in 1837 Gray moved his family there, settling in Houston. In addition to overseeing the interest of Green and Burnley, he opened a law office. Placing himself near the governmental seat provided many opportunities for one of his experiences and talents. From May 2 to September 26, 1837, he served as clerk of the Texas House of Representatives. Then, from April 9 to May 24, 1838, he functioned as secretary of the Senate. After the Texas Supreme Court began hearing cases, Gray served as its clerk. His successful performance in each successive position, bolstered his reputation as a gentleman of style and substance. He was an active Freemason and a faithful Episcopalian. Indeed, he was a charter member of Christ Church–now Christ Church Cathedral–the city’s oldest extant congregation. He also participated in the life of the mind, becoming a founding member of the Philosophical Society of Texas, of which he became secretary. In Houston City he quickly regained the status he had lost back in Fredericksburg. He reached the pinnacle of his professional attainments when, on May 13, 1840, President Mirabeau Lamar appointed him Harris County’s district attorney.

While William was advancing professionally, Millie struggled to adapt to her new surroundings.The first sight of the “precocious city” almost overwhelmed her. A privileged daughter of the Old Dominion, she felt like a peacock trapped in a hen house. “My heart feels oppressed & it requires an effort to wear the appearance of cheerfulness,” she explained. “I could (if I were a weeping character) sit down & fairly weep.” One visitor to Houston City likened it to a “wretched mudhole.” Mrs. Gray concurred: She complained she “never saw anything like the mud here. It is a tenacious black clay, which can not be got off of any thing without washing–and is about a foot or so deep.” President Sam Houston’s namesake capital was not only squalid and ugly, but also disease ridden. Millie logged in her diary that yellow fever infected one-third of the settlement’s citizens. The epidemic killed as much as twelve percent of the municipal population.

Concerning local ailments, Millie became something of an expert. Millie’s diary lamented the occurrence of “Sickness–Sickness–Sickness all around and many deaths.” Soon after their arrival in Texas, an unidentified illness visited every member of the family, including household slaves. For two full months, the mystery malady confined Millie to her sick bed. An anxious mother recorded, “Poor Charlie suffered severely.” On September 8, 1839, her daily entry noted that four-year-old Alice was “still quite sick.” Almost miraculously, all the Grays survived their ordeal. Still, affliction marred their first year of residence in Houston City.

Regardless of the esteem of his community, his perseverance, and work ethic, Gray never achieved the fortune he hoped the move to Texas would bring. Writing to President Lamar applying for appointment as district attorney, he confessed, “My main object in seeking this office, is to endeavor to achieve, through a diligent discharge of its duties, a provision for my family which my present business denies.” His desperation was palpable. Despite his many contributions, solvency eluded him.

Yet, he never stopped trying to attain it. Gray was attending a session in Galveston when he caught a cold. Following his return to Houston, it developed into pneumonia, for which in that time and place there was no remedy. William Fairfax Gray, the chronicler of early Texas, died on April 16, 1841, at fifty-four years of age.

His afterlife was almost as peripatetic as his living years had been. His family laid him to rest in the Old City Cemetery–the modern-day Founders Memorial Park. Following Millie’s death in 1851, his children moved his remains to the Episcopal Cemetery so their parents could lie next to each other. In 1872, Gray’s sons moved the remains of their parents yet again. This time, to Houston’s Glenwood Cemetery, where thankfully they reside to this day.

But now let’s shift our focus to Gray’s crowning achievement: the diary which we celebrate this evening.

The Diary

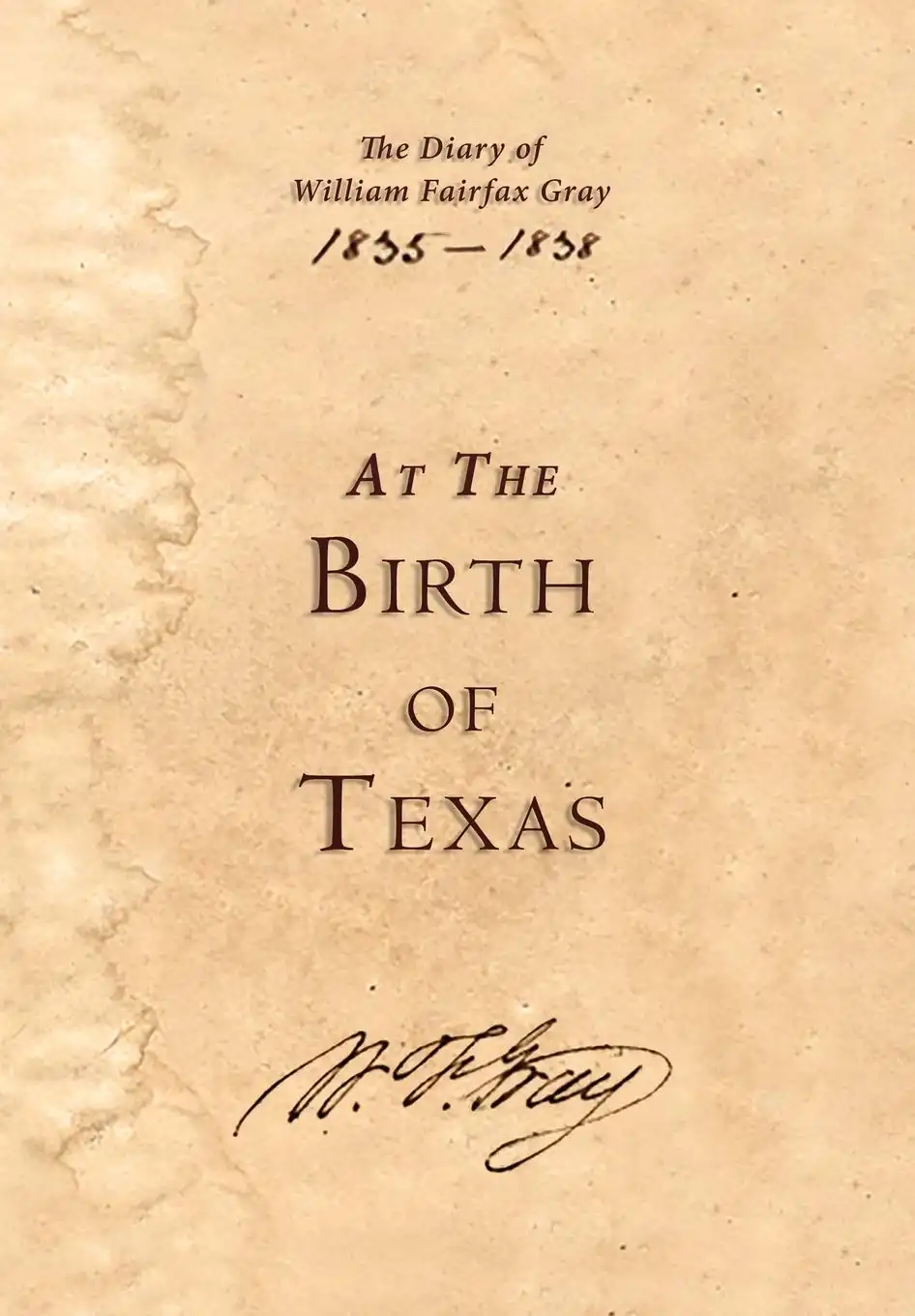

Gray’s diary opens in Virginia on October 7, 1835, and continues until his return on June 26, 1836. A second diary recounting another Texas journey covers the period between January 17 and April 8, 1837. The Colonel carried with him several blank volumes, in which daily entries recorded his activities, expenditures, and impressions. When he filled the pages of one volume, he began another, carefully numbering each notebook in chronological order. The handwritten descriptions of his two Texas journeys eventually filled twelve albums.

Although Green and Burnley had commissioned the diary, Gray’s children maintained possession of the original holographic manuscript. The Virginia speculators were far more interested in Texas real estate than Texas history. It was serendipitous that the diary remained with the family; William and Millie’s youngest offspring, Allen Charles Gray, became a printer. He increasingly became concerned about the deterioration of the original notebooks. As he noted:”Having occasion to examine my father’s record of his experiences and observations during his visit to Texas in 1835-36, I found the ink of a large part of it so faded and dim as to render it certain that in a comparatively short time it would become unreadable. I felt therefore that prudence required it should be put into a more durable form, to preserve the information contained in it for the benefit of his descendants, and possibly for the use of the future historian.”

In 1909, A. C. Gray published his dad’s notebooks as From Virginia to Texas, 1835: Diary of Col. Wm. F. Gray, Giving Details of His Journey to Texas and Return in 1835-1836 and Second Journey to Texas in 1837. One should note that the son concocted this impossibly cumbersome title; his father had never bothered to title his journals. The Houston firm of Gray, Dillaye & Company, Printers released the book, which included a preface by A. C. Gray. Instead of hard boards, paper wrappers contained the contents. It was not a prestigious publication.

Nevertheless, readers recognized its value and quickly snapped up copies of the first edition. We don’t know the number of the first print run, but it could not have been extensive. Corresponding with E. N. Gray in 1919, collector Samuel Erson Asbury lamented that copies of the 1909 edition were virtually unobtainable. Asbury believed that a shame since, “There is nothing to compare with Gray’s Diary for graphic and detailed pictures of the time.”

The family finally understood the value of what they had and made plans to publish a new–and better–edition. In 1935, the Steck Company approached the family with an offer to produce a second edition. George N. Sears wrote to his cousin Dr. E. N. Gray, urging him to hold out for more recompense than the Austin publishing house was proposing. He also suggested that the family ought “to have the Diary properly edited.” That would include adding an introduction, annotations describing the “minor personages of the revolutionary period,” and commissioned maps “to delineate Colonel Gray’s travels.”

At length, Sears addressed the elephant in the room. For years family members had whispered behind their hands that in the 1909 printing, A. C. Gray had judiciously removed passages from the Colonel’s holographic manuscript that were critical of many early Texas heroes. In those days, influential Texans became upset, even litigious, if one presumed to besmirch the honor of their dead relatives. (In some circles, they still do.) Sears allowed how “Uncle Charlie” had made “certain deletions . . . from his father’s account.” If a new edition did transpire, Sears argued, it should follow scholarly practice and reflect what William wrote–exactly as he had written it. It became a moot point. Steck Company backed out of the deal and a second edition did not appear. At least, not at that time.

The following decade witnessed the Grays suffer a devastating loss. Requiring hard cash to pay pressing debts and estate taxes, the widow of Dr. E. N. Gray sold the original manuscripts to collector Earl Vandale. The Colonel, who, in 1834, had to auction off his library, would have understood the necessity. The twelve notebooks became part of the Vandale Collection at the University of Texas, where they remain to this day.

A second edition eventually materialized, but not until 1965. The Fletcher Young Publishing Co., of Houston, released a facsimile reprint of the 1909 edition. Yet, it was not an exact facsimile; this version featured sturdy buckram boards instead of flimsy paper wrappers. It also included a new prologue by Karen Sagstetter, which bibliophile and bookseller John H. Jenkins asserted contained “numerous inaccuracies.” This printing constituted a lost opportunity. The folks at Fletcher Young worked entirely from the 1909 Gray, Dillaye & Co. edition. They made no effort to consult Gray’s original manuscripts, which by then had found a home in Austin.

Not until 1997 did Texans finally get the edition they deserved. Number Four in The Library of Texas series, it was The Diary of William Fairfax Gray: From Virginia to Texas, 1835-1837 (Mercifully, they jettisoned the awkward 1909 title). A publication of Southern Methodist University’s De Golyer Library and William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies, this volume is–by far–the best edition of this essential source. What made this printing so special was the editing of Professor Paul Lack, one of my predecessors at McMurry University in Abilene, Texas. Dr. Lack contributed an Introduction and text annotations which are models of professional scholarship. As he explained in his Introduction: “The original handwritten diaries languished in the Vandale Collection for over half a century without attracting the attention of scholars. They now serve as the basis for this entirely new edition, with text corrected, explanatory notes appended, and maps added, just as Sears had hoped. However, family folklore was wrong about the work of the original publisher–A. C. Gray in fact printed a reasonably complete unexpunged version.” The only criticism that I can levy against this book is that, like all others in the series, it is a limited edition, fine press release. The publisher printed five hundred copies and when they’re gone, they’re gone–forever. The Library of Texas edition is becoming increasingly difficult to find and is expensive to acquire when one does. This book, in this edition, should remain constantly in print.

Since Professor Lack did the most–and best–work on William Fairfax Gray and his remarkable journals, it is only just and proper that he has the last word: “The diary had been kept in compliance with the orders of his employers (Thomas Green and Albert T. Burnley), who had requested a reliable record of observations regarding potential land purchases. Fortunately, Gray recorded his impressions of people and politics as carefully and completely as he did the required investment notations. No other work equals his diary for immediacy, accuracy, perceptiveness, and readability.”

No other work, indeed.