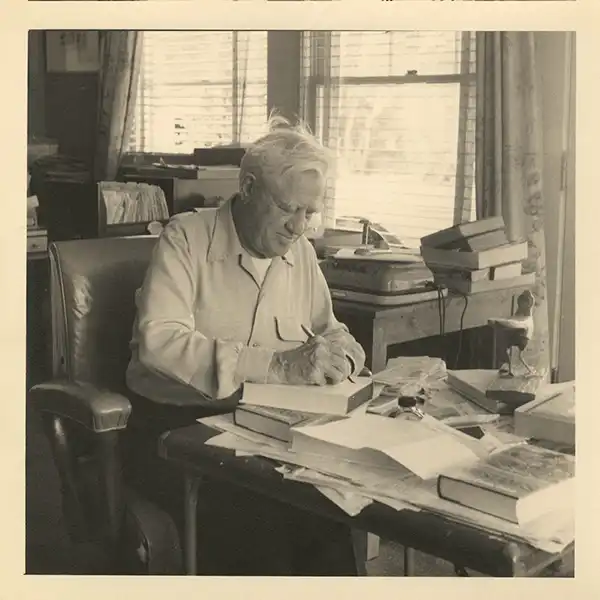

To paraphrase Marc Antony, “I come to study Dobie, not to reproach him.” Let’s get one question out of the way up front. “Was J. Frank Dobie a dirty old man? No, no he wasn’t; not by any stretch of that classification. That said, he did have a healthy fascination with the earthy, bawdy, and off color. Throughout his writing life, he reserved an empty typing-paper box to store naughty bits he came across or that friends, associates, and, sometimes, even total strangers sent him. When the box filled up with letters, notes, and clippings, he figured he’d have enough sources for a book. He shared his passion for sexual folklore with his friend Roy Bedichek, who also kept an archive of risqué resources, which he titled “The Privy Papers of Sitting Bull.” Walter Prescott Webb, the other member of the so-called “triumvirate,” was a bit of a stuffed shirt and failed to share the more prurient interests of his pals—or, at least, not to the same extent. In observance of the values of their time and place, neither Webb, Beddi, nor Dobie ever discussed any of this around women and children.

In the 1950s, what was then called “locker room talk” remained in the locker room—or the deer camp, or the all-male gatherings that Dobie hosted at Paisano Ranch, his rural retreat located fourteen miles outside Austin. As it happened, Dobie never completed the volume, probably because his wife Bertha opposed it. Yet, he did craft a title for the book that never was: Piss & Vinegar.

While the monograph never materialized, Dobie’s research materials for it remain. Following his death in 1964, most of his papers went to the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. On a scorching day this past summer, Deborah and I spent an afternoon pouring over the “Piss & Vinegar” collection at the HRC. No longer in its original typing-paper box, archivists have meticulously placed the various elements in folders inside heavy preservation boxes. Mr. Dobie was either the original conservationist or the cheapest man in Christendom. He took notes on any scrap of paper that came to hand; we found one dirty joke jotted down on the back of a finely printed wedding invitation. Much of the collection consists of ribald passages from classic and modern texts. These included racy episodes from Boccaccio, Chaucer, Rabelais, Richard Burton (this was Sir Richard Francis Burton, the British explorer, writer, and soldier, not the Welsh actor who was from time to time married to Elizabeth Taylor, although he would have been able to contribute to the discussion), D. H. Lawrence, and Henry Miller. Indeed, Dobie claimed that Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover was his favorite modern novel. One gets the impression that Dobie cited—and quoted—these established writers to validate his own research.

Despite his habit of sporadically calling on the Almighty for rhetorical effect, Mr. Dobie was an avowed atheist. Nevertheless, he was full-out evangelical when defending one of his favorite words from the attacks of blue-nosed moralizers. But let Frank speak for himself:

“Call thou nothing unclean.” [Acts 11:9] Surely it is no mark of “unclean lips” to use the word piss than it is to actually piss. Nobody can live without pissing. The word is shorter and more direct than urinate and to me it seems stronger. Nurses speak of voiding, but would as soon say piss if their patients were not so unrealistic. You can take a “specimen” in a bottle through a parlor on the way to a doctor’s laboratory, but you mustn’t call it a bottle of piss. I know various males of the human species—they are apt to hang around universities—who, according to the old saying of the soil, are “so nice they have to squat to piss.” That form of niceness is never an expression of wholesomeness and of sanity in the base use of the word. I think of another ancient expression going back to times when men were familiar with horses and other livestock. This expression calls up a picture and is as clean and strong as wind over a mountain: “As strong as stud piss with the foam blowed off.”

Dobie was an advocate of the word in both its noun and verb form. As an elderly man, he became more concerned with the verb. As he expounded in a 1961 letter to Ned Bradford, his editor at Little, Brown & Company, “It’s a Mexican saying that up to 50 a man wants to make money and after that he wants to make water. The water age comes later with many. I think you should advertise this book among civilized men who have reached the water age.” Some of us are able to empathize.

Dobie’s research into the explicit was not merely literary. It was also cinematic—after a fashion. Tucked neatly into the HRC’s folders is an order form from Enjoyment Unlimited, a firm in St. Laurent, Montreal, Canada. It produced a lurid assortment of what were then called “stag films,” grainy 8 millimeter, black & white films with little of what we’d call “production values.” Across the top of the form, in the barely legible scrawl that passed as his handwriting, “Mr. Texas” had scribbled a note to himself: “a new ad. of the pornography line to me[.]” Boasting titles like “Strip Poker” and “Plumber,” these brief flicks were intended “for your private collection.” The plot of one “masterpiece” was especially gripping. Typed completely in caps, the sales representative expounds:

A YOUNG MARRIED WOMAN FINDS HER T.V. OUT OF ORDER WHILE HER HUSBAND IS ON THE ROAD. SO SHE CALLS A REPAIR MAN WHO PROCEEDS TO FIX THE SET, THEN FINDS OUT SHE HAS NO MONEY TO PAY. OUR HERO BEING ON THE HANDSOME SIDE, SHE THEN DECIDES TO PAY THE ONLY WAY SHE KNOWS.

Back in the 1950s, the discerning collector could acquire this 200-foot art film for a paltry $40.00. Sadly, Enjoyment Unlimited appears to have gone out of business.

I know; I checked.

The collection also contains a great deal concerning Sam Houston. I have studied the man in a serious way for more than thirty-five years, but I had never encountered any of the stories Dobie had accumulated. Indeed, he introduced me to a category that I had never even heard of: “Houstonian apocrypha.” That is to say stories regarding Houston that can’t be corroborated by primary documentation, what my Granny called Old Wives’ Tales. As a professional historian, I can have no truck with such unsubstantiated accounts; as a folklorist, they were Dobie’s bread and butter. Not only were all the Houston yarns unproven, they were to my surprise, also highly indecorous.

I need to tread carefully here as this is a family-friendly venue and tiny ears may be listening. Therefore, I have amended the text to avoid certain words. Still, I’m sure that the sophisticates in the audience—David, Rodney, Taylor—will be able to discern the original vernacular.

The first anecdote professes that the general rode across Texas in a state of almost constant arousal. When, at last, his ardor wilted, he would order a halt and camp on that exact spot. Given this highly dubious account, one must discuss Houston’s root to San Jacinto in an entirely different context.

The second Houston story came into Dobie’s possession courtesy of a 1959 letter from Tom Sutherland, who claimed he had heard it “some years ago in the Huntsville area.” It relates an episode that took place during the days of the Texas Republic. I relate it here almost exactly as Mr. Sutherland related it to Dobie:

Sam and a friend were riding through the country when they were simultaneously overtaken by a call of nature. They dismounted and tied their horses in a grove along the trail; squatted and dropped britches, each man bent upon his business.

Before either had finished, however, a company of women, sun-bonneted and carrying buckets, came down the trail from berry-picking. The ladies invaded the privacy of the two gentlemen unaware and without warning. Sam’s companion bolted into the bushes, but the General merely shoved his large hat over his eyes without visible perturbation. The ladies, when they perceived the stranger and his activity, stamped out of sight with a few sounds of surprise.

When he had emerged from the bushes and recovered his original composure, Sam’s friend turned to Sam with a not unnatural question. “Sam,” he asked, as they mounted again, “why in tarnation did you sit there in front of them women?”

“Why not?” said Sam. “My hat was over my face, and there’s darned few women can recognize Sam Houston by his tushy alone.”

Another fable takes us into the presence of the great man on his death bed in 1863, while the Civil War still raged. It came to Dobie by way of Tom Love. Frank left a typescript just as he heard it from Mr. Love:

Tom said when Sam lay pretty close to death, . . . [Francis Richard] Lubbock came to see him. [Lubbock was then governor of Confederate Texas. Deposed former Governor Houston was, of course, notorious for his Unionist sympathies.] Lubbock said it would be too bad if two great men like ourselves who had had so much to do with the history of this glorious state of Texas should come to an end without [resolving] the differences between them. Sam said, “Oh, well, that’s all right. I’m glad you came by.”

“Now,” Lubbock said, “I want to do something to signalize the renewal of our ancient friendship, which was so cruelly interrupted by some of the things you said about me, and possibly partly because of some of the things I said about you. Is there anything I can do for you? They tell me you won’t be here very long” (he was a cheerful sort of fellow).

Houston said, “Yes, there’s something I want you to do for me.”

“What is it?”

“I have a hard time turning over. Will you turn me over?”

Lubbock turned him over. Sam said,

“Now, lift up my nightshirt and kiss my black heinie, you son-of-a-gun.”

J. Frank Dobie was a fully rounded human being. The late Don Graham, a good friend and a Dobie Dichos presenter, whom I sorely miss, perhaps said it best:

In the end, Dobie, Webb, and Bedichek were men, as Dobie would have said, “out of the old rock.” They prided themselves on their connectedness with the earth, for which they have been much celebrated, and to that I would add their connectedness to earthiness, a humor that Chaucer, Rabelais, and Henry Miller, among others, would have admired.

They would have esteemed Dobie most of all. For he was a man—a natural man. As natural as stud piss.

With the foam blowed off, of course.