The Word That Explains it All

Torrents of Allied bombers hammered Hitler’s Third Reich. In the autumn of 1944, diminishing numbers of Luftwaffe personnel pitted their Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs against insurmountable odds. In the skies over Germany, the elite Jagdgeschwader 54 spied an American P-47 and pounced, driving the aircraft dangerously near the deck. “The [enemy] pilot was as brave as a lion,” noted Oberleutnant Willi Heilmann. “At barely 60 feet he performed a roll, trying to slip away to one side.” Nevertheless, Heilmann’s wingman clung to his adversary’s tail as “tracers pounded relentlessly into the Yankee’s fuselage and the Thunderbolt hurtled into a field.” The pilot survived the crash but ground troops soon captured him.

The chivalrous Heilmann rushed to meet his captive adversary. Arriving at Achmer airfield, he found the prisoner already under interrogation. “He was an unpleasant looking immature boy of about twenty with a dirty uniform and unshaven,” Heilmann recalled. “Impertinent and cynical, chewing gum between chattering jaws, he gave incomprehensible replies.” Most of his responses were evasive. Yet, to one question, he replied loud and unmistakable. Oberleutnant Heilmann left shaking his head: “Texas,” he muttered, “this word seemed to explain it all.”

Why?

How could a single word provide insight to one whose home was, not on the range, but deep in the heart of Nazi Germany? Texas—the name and state of mind—was, even then, a global metaphor. “The word Texas becomes a symbol to everyone in the world,” novelist John Steinbeck insisted. “There’s no question that this Texas-of-the-mind fable is often synthetic, sometimes untruthful, and frequently romantic, but that in no way diminishes its strength as a symbol.”

Some, of course, rejected such inflated assessments. Texans were, historian Joe B. Frantz declared, “bright and dumb, conservative and liberal, tall and short and slim and fat, courageous and cowardly—just like the people in Connecticut and Oregon.” Yet, with all deference to Professor Frantz, here’s the difference; no one ever spoke of the “Mythic Connecticut” or the “Oregon Mystique.” Minnesota was not the word that explained it all to Oberleutnant Heilmann. Nevertheless, merely asserting the existence of Texas exceptionalism fails to address the more profound question. How did this phenomenon occur?

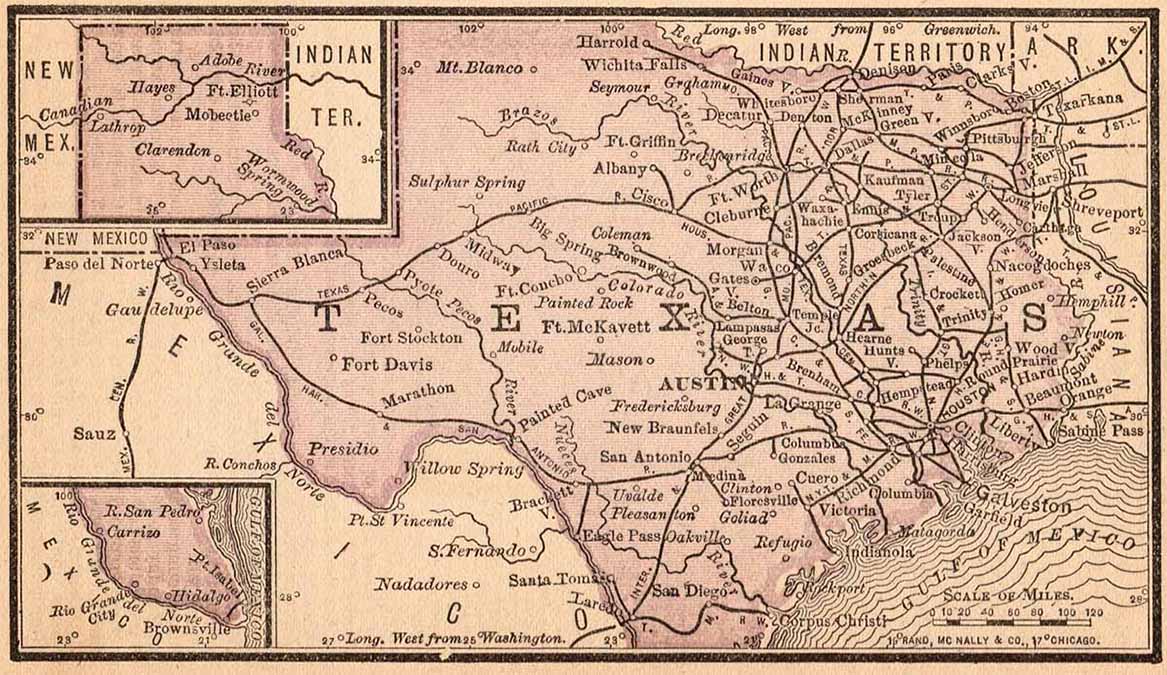

History provides the answer. It also shaped a singular people and culture. Spaniards, and after 1821, Mexicans, valued Tejas only as a defensive barrier against French, British, Indian, and finally American encroachments. Tight-fisted officials dispatched clerics, soldiers, and settlers to the frontera, but never in numbers sufficient to achieve dominion or provide for their safety. Removed by distance from the seat of vice regal power in Mexico City, colonists of Tejas learned to fend for themselves. That de facto abandonment nourished a culture independent from the rest of New Spain. Tejanos developed their own customs, clothing, music, tactics, food, even a variant of the Spanish language. When officials ventured into Tejas, they found them unfamiliar and disreputable. “The Mexicans that live here are very humble people,” inspector José María Sánchez recorded in 1828, “and perhaps their intentions are good, but because of their education and environment they are ignorant not only of the customs of our great cities, but even of the occurrences of our Revolution.” Sánchez was reluctant even to acknowledge Tejanos as fellow countrymen: “One may truly say that they are not Mexicans except by birth, for they even speak Spanish with marked incorrectness.” Texas exceptionalism visibly flourished long before Anglo-American immigrants arrived.

That’s not to say that norteamericanos did not add to the mix. The Panic of 1819 devastated many frontier families. Reports that Texas had lowered barriers to American settlers seemed a godsend for poor folks seeking a place to start over. And it was. The “Old 300” families struggled in the beginning but by 1828 Empresario Stephen F. Austin could crow to his brother-in-law: “This is the most liberal and munificent Govt on earth to emigrants—after being here one year you will oppose a change even to Uncle Sam.”

He did not exaggerate. The Mexican government was so openhanded that newcomers could hardly believe their good fortune. A typical family, if farmers, received one labor (177.1 acres) or, if they declared themselves stock raisers, a sitio (a square league or 4,428.4 acres). Consequently, few immigrants admitted to being sodbusters. Land-hungry Americans may never have owned a horse or punched a steer, but once in Texas they became “ranchers.” Indigents who had arrived in Texas poor as Job’s turkey built spreads ten times larger than those back in the “old states.”

We’ve all heard it. “Everything’s bigger in Texas.” The enormity of Mexican land grants was likely the source of this popular adage. It may be a myth, but the state is still larger than France. Even so, the “bigger-in-Texas” cliché misses the point. It’s not the size of their ranches, or Cadillacs, or Stetson hats, or belt buckles that define Texans.

It is the size of their dreams. Texas provided scope for ambitious visionaries: the Richard Kings, the Charlie Goodnights, the Clint Murchisons, the H. Ross Perots, the Mary Kay Ashes, the “Red” McCombs—dreamers and schemers who savored the doing more than the payoff. What proved impossible elsewhere became feasible west of the Sabine River. That spirit remains alive, the reason non-natives are currently moving to the Lone Star State at the rate of 1,200 a day.

From the beginning, cultures clashed at this crossroad of empires; some came to settle, others to slaughter. Mayhem and carnage rendered the region one enormous battlefield. Thus, the warrior myth entrenched itself in the public imagination. Are Texans really more belligerent than others? Perhaps so. Given their history, how could they be otherwise? Yet theirs is rarely the mindless violence of the thug, terrorist, or sociopath. “Texas,” Steinbeck observed, “is a military nation.” Natives of the state pack the ranks of the national armed forces and military installations dot the landscape. Are Texans more pugnacious, or simply less willing to stand idle while miscreants abuse their rights, slight their honor, and practice bad manners? “I hate a man that talks rude,” explained Larry McMurtry’s Captain Woodrow F. Call after beating an army scout to a bloody pulp. “I won’t tolerate it.” To most Texans, that makes perfect sense.

Unlike most Americans, Texans remain rooted to their hardscrabble soil. “We’re still tied to a place,” declared native son Tommy Lee Jones. “We happen to think it’s important to be from some place.”

Texans, having witnessed what individuals breathing the fresh air of freedom can attain, bristle under restraint. Their tendency to strike an independent course, to observe their own customs, annoys foreigners. Novelist Stephen Hunter leveled the criticism through a fictional character, but outsiders frequently concur: “These damn Texans. They couldn’t do anything but by their own rules.”

Correct.

Potentates and politicians living in remote capitals, bureaucrats who knew nothing of conditions in Texas, have always tried to foist one-size-fits-all policies suited for places with milder climes, for persons of more yielding dispositions. They never worked; they never will. Texas—and Texans—are simply too different from those other places and those other people. Like Captain Call, they won’t tolerate it.

There is integrity in tradition, value in the verdict of experience, of lives lived, and principles cherished. It does not venerate the ashes, it feeds the flames. And Texans heat multiple irons in that fire. Explain to the heirs of Tom Green, Leander McNelly, and Heman Marion Sweatt that compliance is a virtue, submission but another form of patriotism. Texans have spent enough time in cattle pens to recognize this notion for what it is—and their mamas taught them to scrape it off their boots before they came into the house. Ultimately, identity remains the best argument for Texas exceptionalism.

It’s just this simple:

If a people decide that they’re different, they are.