It’s whimsical.

Not until my physician diagnosed me as diabetic did I develop a genuine interest in food. Please understand, I’ve always loved to eat, but in that BD (before diabetes) part of my life, I ate promiscuously. I was a food slut. Pie, candy, turnovers, cinnamon rolls, fast food, you name it: if it looked good or smelled good, I pounced on it. Then, with remarkable suddenness, I had to terminate my pernicious affair with sugar as one must occasionally jettison a troublesome girlfriend. Perforce, I became more discriminating in my food choices. It was then, that my wife Deborah and I discovered historic dining.

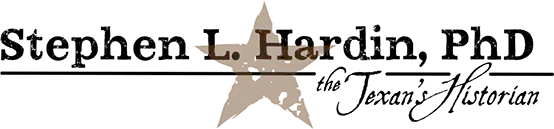

On a trip to Philadelphia, Deb visited City Tavern and discovered the joys of eighteenth-century cooking. So impressed was she, that she purchased Chef Walter Staib’s City Tavern Cookbook: 200 Years of Classic Recipes from America’s First Gourmet Restaurant. What a revelation! History had always fascinated me, but Chef Staib taught me that what our ancestors ate—and how they prepared it—defined them as much as (probably more than) how they voted, how they fought, and how they dressed. Consider how much of what people eat, where they eat, and how they eat characterizes their “lifestyle”—however one chooses to define that reprehensible expression.

I began incorporating preparation of historic recipes into the curriculum. I required that my students prepare a selection from Chef Staib’s cookbook and then participate in colonial dinners that Deb and I hosted. The assignment spawned much hand wringing and teeth gnashing; students carp when their professors hurl them out of their comfort zones. Do it anyway. Before sitting down to dine, students explained what they had learned during the preparation of each dish. While not every venture was equally successful, each was, at least, eatable. The most common comment was, “I’ve never tasted anything like this—but I like it.” Students began to grasp that their ancestors were different from them. If we who occupy the present are to understand the past, we must come to terms with those variations. When my students duplicated historic recipes, they learned how different their forebears were. They also discovered that their food choices were just as valid as theirs, and just as good.

In addition, to the food, Deb and I attempted to create an eighteenth-century setting. It was the first time many of these young people had ever dined by candlelight. Notwithstanding all the bellyaching beforehand, almost all of them confessed that the colonial dinner had been the most memorable, and edifying, portion of the class.

If you’re reading this website, you have at least a passing interest in the past. Extend your curiosity to historic dining. You will gain an appreciation for the people and their time and place that you might not have thought possible. Not only can we walk in their footsteps, we can also feast at their table.

Bon appétite!