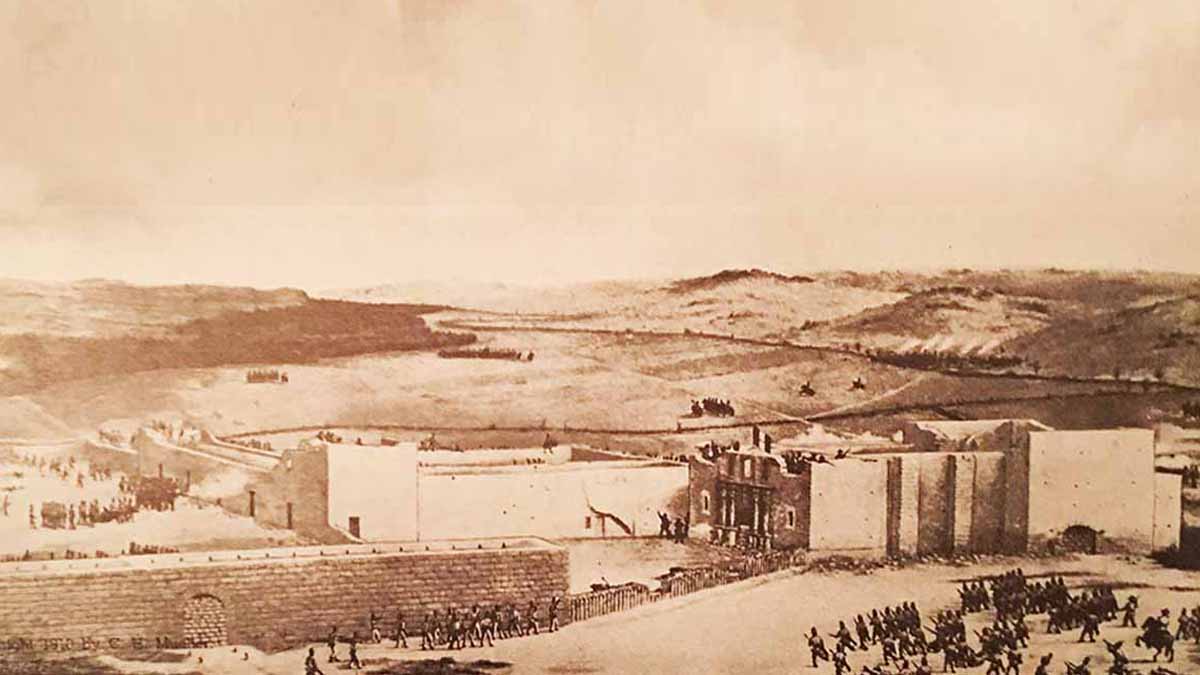

The Alamo enjoyed a rich and vibrant history even before the pivotal battle. Moreover, despite what the movies tell us the Alamo was never abandoned, nor was it in ruins before 1836.

In 1690, responding to the French expedition of Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, Spanish officials establish the first mission in East Texas: San Francisco de los Tejas. Lack of supplies and the mounting hostility of native converts force the missionaries to abandon their efforts in 1694. In 1716, Captain Domingo Ramón returns to the Piney Woods. He has learned from the earlier effort; this time he constructs a series of mutually supporting missions, along with military garrisons to defend them. These establishments have two mandates: convert the natives and keep the French out of Spanish territory. Yet, the vast distances between the East Texas missions and settlements on the Rio Grande remain an obstacle.

In 1718, an expedition led by Martín de Alarcón arrives in the San Antonio River Valley to establish a mission—San Antonio de Valero—and a presidio—San Antonio de Béxar. The goal is to missionize the local Indians, but also to establish a way station for mule trains midway between the Rio Grande and the far-flung East Texas Missions. These are the origins of the town of San Antonio de Béxar, which later becomes the social and political hub of Spanish Colonial Texas.

At the time, more than one hundred native groups inhabit the area in and around the San Antonio River. Among these are the Coco, Ervipiame, Karankawa, Pamaya, Payaya, Pataguo, Sana, Tacame, Tamique, Top, Xarame, and Yuta tribesmen. All hunter-gatherers, modern scholars group them under the collective label of Coahuiltecans. They are the residents of San Antonio de Valero and provide the labor necessary to make it successful.

The mission endures its share of obstacles. Father Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares initially constructs the mission along the banks of San Pedro Springs, a site that later proves susceptible to flooding. Before arriving at its current location, the facility moves three times. In 1724, a hurricane destroys or damages most of its structures. Despite the presence of the presidio soldiers, Apache raiders hound the mission’s occupants. Even worse are attacks of smallpox and measles in 1739, which ravages the native population.

The decades of the mid-eighteenth century see Valero’s greatest success. In 1745, it housed 311 converts; by 1756, that number reached 328.

Yet, the years following 1756 suffer a steady decrease in the mission’s population. The outcome is inevitable. In 1793, Spanish officials order Valero secularized. Franciscan padres mete out animals, quarters, lands, and tools among the few remaining natives and San Antonio citizens.

Spanish authorities may have secularized San Antonio de Valero, but Béxar residents never abandon it. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, many of them have taken possession of its lodgings, transforming the mission into something resembling an apartment complex. In 1803, the Second Flying Company of San Carlos de Parras establishes its headquarters inside the walls of the former mission. These troopers are residents of San José y Santiago del Álamo, near Parras in southern Coahuila. Understandably, Bexar residents soon shorten the lengthy title to La Compañía del Álamo, or simply El Álamo. Through its association with the flying company, locals begin calling the former Mission Valero, the Alamo. At one time, more than two hundred personnel attached to the military community live within the compound. Some take over billets inside the walls, while families construct huts. Unmarried soldiers bunk on the mission convent’s lower floor—the Long Barracks. The companies of Nuevo León and Nuevo Santander later join the Álamo de Parras Company. From 1805 to 1812, Béxar’s first hospital also operates there.

Far from being an abandoned ruin, the former San Antonio de Valero—now simply the Alamo—continues to play a vital role in the affairs of the Béxar community. From 1810 to 1821, the town becomes embroiled in the tumultuous events of the Mexican Revolution. When Mexicans finally win their independence from Spain in 1821, Béxar and its people become part of the fledgling Mexican Republic. During the 1820s and early-1830s, immigrants from the United States begin arriving in Béxar to conduct business with government officials. Others like James Bowie, Samuel Maverick, and Erastus “Deaf” Smith take up residence. By 1834, it is apparent that trouble is brewing between Tejas and the dictatorial regime in Mexico City, but few can imagine the part the Alamo will play in the coming conflict.